11 February

This story is heavier.

In Kenya there is no winter, spring, summer or fall. There are dry seasons and rainy seasons. Sometimes the rainy seasons don’t come, or are late, and there is drought. At other times, they won’t stop, and there is flooding. On. Off. Life. Death. Dry. Rainy.

I arrived at the gates to the University early because I was too excited to sit in my house waiting. I was not sure we could communicate, as he is not allowed to have a mobile phone with him while he is on the grounds of the private high school that he attends north of Nairobi in Thika. I rejected Kenya time and used my American sense of time to arrive early and wait just in case we couldn’t communicate. I did not want to run the risk of missing him and not knowing how to find him.

I had texted back and forth with his teacher and principal to arrange permission for him to be released from school for the day. He is in classes six days a week, including Saturdays, and he gets up every day at 3:00 a.m. He has extremely early morning homework time, and then school chores, and then classes. They are required to be in their rooms by 9:30 p.m. to end their day. He wears a school uniform at all times, including a tie. I have found discipline in Kenya.

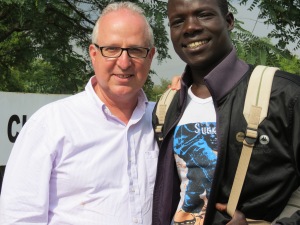

I first spotted his smile. There he was, his six-foot frame striding down the road, a huge grin on his face. In this setting I am never hard to find. In this setting, with hundreds of Africans coming and going through the school gates, he too was not hard to find.

I found Ojullu.

It couldn’t have been planned. After a whirlwind trip to Kenya with students to make theatre with refugees with The Dadaab Theatre Project and the Great Globe Foundation and the United Nations in 2011, I never dreamed I would return to Kenya. But it seems I was destined to return. That I was visited on two successive days on the campus of Kenyatta University by members of the refugee theatre group who I had worked with so briefly almost three years ago could never in a million years been coordinated or planned. Not in Africa.

At 24, Ojullu is determined to be educated. He has been in school near Nairobi for the past three years, away from the refugee camp, determined to get a high school education. He is among the oldest boys at school, and his life is complex, mixed with boys much younger from different kinds of families. He values his education more than anyone I know.

He brought his school friend with him on my invitation, a 23-year old young man named Angango. They are both orphaned, both on their own, both making education a priority when others their age and in their situations might have given up. Angango is a Prefect, which means his job as a school boy is to run one of the two dorms for those who board on campus as well as being a student. It is an unpaid honor. Ojullu has been named Head Boy, the top honor, and that means he supervises the prefects and acts as the student leader for the school. Their ties get to be different than the other boys, who must wear red ties. They are Kenyan Harry Potters.

They too had never been to Kenyatta University, and they looked at home striding across campus.

How can I explain the emotion I feel looking at these young men, who should be college graduates by now had life given them different paths, who have thrust their beings into succeeding in high school, now, at all costs, no matter their age?

Ojullu is a writer, an actor, a creative artist, a very deep well. His smile is large, and the pain underneath is even larger. He is fearless and generous, devoted and loyal, sensitive and proud. He is Ethiopian, from the Gambela tribe, and poetry courses through everything he says. He speaks more sparingly, feels more deeply, and I slowly learn to listen to his silences. He graduates at the end of this calendar year, and he wants to go to University to study acting and drama.

The students in Cincinnati at CCM where I teach wanted to support my Kenya trip with a benefit to raise money for something African and I said ‘raise funds for the Great Globe Foundation to help keep Ojullu in school.’ On a cold and snowy night at the end of last semester I sat in an old church in Clifton, at my first Carols For A Cause, organized and run completely by American college students, and Ojullu felt so far away. To make Ojullu more real I gave them a poem he had written to read to the audience and participants.

After performing in front of an audience for the first time in May 2011 for UNHCR Korea and tasting chocolate for the first time in his life, Ojullu wrote this poem in response to the experiences.

This Day

Ojullu Opiew Ochan

What will this day be to me?

How do I call it?

The day that made me know

That I am human being.

The day that make me realize

That I am a part of people.

The day I taste chocolate.

The day that open a new world to me.

The day that make my heart

Overflowed with joy.

Even if I am on my bed, I still

Remember my team work.

How do I call this day?

I will call it whatever I have to

I will call it anything.

It is the day that I am inspired

That I can make a difference.

In my living room in Kenya in my ranch house on my dead end street in the back corner of a thousand acre campus home to more than 40,000 students Ojullu read a new poem to me on Sunday. He read it once, and meant to leave me with a copy, but it departed in his backpack by mistake. It was a poem of struggle, honest struggle, and I am haunted by the refrain he repeated:

“BUT THE RAINS WILL COME. THE RAINS WILL COME.”

Ojullu has hope. The rains will come.

I served Ojullu and Angango the same meal as I served Chapter One, but I gave them a snack tray earlier. ‘What are these?’ I was asked. ‘They are grapes,’ I replied. I watched two young men enjoy red grapes for the first time. That is something I never expected to witness in my life. I saw the innocent joy of men eating grapes for the first time.

We cooked together, and Angango dared to step to the stove first to stir the leftovers as they heated. They were a team, and I saw a child-like pride. For the second day in a row I had men in my kitchen who never cooked, who culturally and socially had no reason to cook. My expensive chicken nourished more than our stomachs. Ojullu seasoned the meal with seasonings courtesy of Mrs. Dash.

These boys knew genocide; these men are strong. I heard stories while we ate of trouble with police, of the need for identity papers, of regulations and unfairness that keeps people down, of knife attacks.

I walked them back to the University gate and the spiked iron bars that encircle the campus, through the metal detectors, back out to the Thika Highway, and the wildness of Nairobi and the matatu ride back to their secondary school. They changed their clothes off campus to visit me, and must return to their school uniforms before they can re-enter school grounds.

I watched the departure of these men, these boys, these men, and deep inside I know their rains will come. After the drought, their rains will come.

I walked back to my house in the rain.

I am speechless. Richard, this is just beautiful. Thank you so much for writing this and with such grace honoring our friend, Ojullu. He is a mighty force. and so are you.

How strong they are to HAVE hope. And the rain came… magical.